Two years ago, I had just begun research on The Flight of a Butterfly or the Path of a Bullet?: Using Technology To Transform Teaching and Learning (2018). Mary Jo Madda, then Senior Editor at EdSurge, interviewed me for a podcast and column in EdSurge. I had been observing lessons of exemplary teachers who had integrated technology into their daily lessons seamlessly. The edited interview appeared herein February 2016.

Q: Larry, thanks for sitting down with us. You’ve a lot of references and titles—you're a researcher, a professor, a former teacher, a blogger. But who do you consider yourself first and foremost?

I would call myself a teacher at different levels. I’ve taught in high schools, I’ve taught at the university, and I teach through my writing. You teach through writing because you’re getting ideas out there, and if it’s a post on a blog, you’re getting comments and you can have a back-and-forth. It’s not the same as a face-to-face interaction, but it’s the next best thing. You’re starting a conversation, and you never know where it’s going to go... I call writing a form of teaching because it’s another way to get ideas out in the arena and have interactions with people.

Speaking of your writing, when I talked to some of my team members, they said they like reading your blog because they sense a note of “fresh cynicism” when it comes technology. So, your honest opinion. The growing interest in edtech—how do you feel about it?

What’s happened is that the interest in classroom technologies has accelerated and expanded, but remember—the desktop computers came out thirty years ago. The first Apple, the Atari, those Macs came out in 1981-84, and it exploded. But the access on the part of teachers and students was very, very limited for the first 15-20 years. In the 1990s with laptops coming out, it really accelerated.

But I think what has given edtech a huge push has been the larger reform ideology, which is informed by business interest and trying to increase public schools efficiency and effectiveness. That was triggered a lot by the Nation at Risk Report (1983), where basically the CEOs of the nation combined with civic leaders said, “American schools are lousy.” They used international test scores as proof. Well, technology was going through the economy and changing the job structure and industries. So, the application of technology to public schools seemed natural.

When the money became more and more available, and as the technology improved student access, you had not an “explosion” but rather an “evolving” interest in technology that fit in with the reform ideology.

So the two—reform ideology and technology—mutually catalyzed each other?

Exactly. It started with the assumption that public schools were failing… and that the application of efficiency devices and attitudes were what schools needed. And we’re still there!

The pattern of hype leading to disappointment, leading to another cycle of overpromising with the next technology, has a long history to it.

In all of this history, do you see more evidence of failure with technology or promise with technology?

Well, I’m not a cynic, as your colleagues say. I’ve never been a cynic. I wouldn’t be in education. To be cynical means that the disappointment is so severe, and you have no energy to do anything about it. I’m skeptical. Being skeptical is very different. Skepticism and curiosity are very close in my mind.

I’ve been skeptical of technology because the early technologies in schools that I studied began with the film. That morphed into radio, instructional television, and then the computer. By looking at all the hype that surrounded each one of these, the access to those early ones was very limited. When I started teaching history in high school, there was one 16mm projector in the department’s store room, back in 1956. The pattern of hype leading to disappointment, leading to another cycle of overpromising with the next technology, has a long history to it. If I cite MOOCs… that’s just the most recent incarnation of hype in technology.

There are a long of things about teaching that can be automated. A lot of teachers’ administrative stuff—like attendance and gradebooks—can be very helpful. But to replace teachers? No.

I get the question constantly of whether technology will ever replace teachers. Can teachers and edtech coexist peacefully?

If you look upon teaching as a helping profession like medicine, social work, psychotherapy… those are completely dependent upon interaction. Now, all of those have had new technologies applied to them. But if you believe that teaching is anchored in a relationship between an adult and a student, then that can’t be replaced.

Now, there are a lot of things about teaching that can be automated. A lot of teachers’ administrative stuff—like attendance and gradebooks—can be very helpful. But to replace teachers? No. That’s a rosy scenario that borders on fantasy.

Look, you’ve got cyber charter schools, and some of them are for-profit. There’s a lot of evidence that shows that they’re trying to eat at the trough of public funding. But the nonprofit virtual schools and a lot of online schooling provide services for different groups of people that are isolated or have full-time jobs. I think that’s terrific! But that will not replace teaching. When I was a superintendent, personnel was 70% of the budget. The dream of cutting back on that, of making education less expensive, now that’s hardly talked about publicly. But that’s part of the rhetoric surrounding online instruction in schools.

Now, let’s talk about where you are right now. Back in January, you laid out your reasons for shifting focus from disappointments and failures in use of new technology to best cases of such use in districts and classrooms. Why the change?

Well, I’ll be a skeptic until I go into the ground. But in reading about teachers who are using technology, another way to find out about the strengths and shortcomings of edtech is to look at best cases. The disappointments and failures won’t go away because technology is so embedded in our culture as a positive good that there will always be overpromising. I’m more interested in the best cases, and I want to see them at the classroom level, at the school level, and at the district level. There are individual teachers who are exemplars that anyone who loves technology would embrace. But whether you can scale it up to a school, that’s harder… and then at a district, that’s even more difficult.

I’ve been in this area for 30 years, and I know a lot of people. Currently I’m in the San Mateo High School District, and I’ve been observing some teachers. And then I’ve contacted Dianne Tavenner, founder of Summit Public Schools, who was a former student of mine. When I had this idea, I contacted her and she welcomed me in. And then another friend of mine runs an upscale, private Catholic school. She was talking about the cultural principles that motivates a Catholic school, and whether technology reinforces that, undercuts it… I think that’s very interesting.

You know, it’s funny. I came here expecting I was going to get a lot of answers, but I’m coming away with more questions!

Well, that’s the difference between skepticism and cynicism. Cynics have the answers; I don’t have answers. I have a lot of hunches.

I don’t believe that there is a technical solution to teaching, to running a school, to governing a district. Education is far too complex.

What’s fascinating is that we just featured Dianne Tavenner on the EdSurge podcast in a debate about personalized learning. That must be coming full-circle for you! And I have to ask—do you believe in personalized learning with technology involved?

Well, I want to see it at work at Summit. I had a nice conversation with Dianne and CAO Adam Carter, and I was really taken with the fact that they came to [technology] very late as a way of dealing with an issue that crept up on them. [Years ago] they graduated all these kids to go to college, and just over half are finishing. What I admire about what Dianne and the staff is doing was that they said, “Let’s take a look at what we’re doing to see how we can strengthen the experiences of kids while they’re here, so that they’ll have the skills and attitudes necessary to finish college.” And that’s where personalized learning comes in.

Before I let you go, my final question has to do with entrepreneurs and investors—the people that are making and funding the tools. You’ve mentioned technology not being the be-all, end-all. But are tools being made without the users in mind?

Well, that’s been a pattern in the industry. There are some startups and firms that are user-friendly. Dianne told me that Facebook sent four software engineers over to Summit, and the engineers started with “We don’t know what you guys know, so we have to learn from you.” That’s very rare in my experience.

Getting back to your question, I see it as a fundamental dilemma. There is a clashing of two highly-prized values. There’s the desire for profit—you’re not going to give a small company $10 million unless you believe there’s a 1 in 10 chance that it’ll pay off. The other is the highly-prized value that technology is indeed the answer to educational problems. People believe that deeply. A lot of venture capitalists believe that. People who do startups in the education realm believe that. I’m not critical of that—that’s a belief system. But when it comes to schools, the complexity of teaching and the complexity of relationships is not often thoroughly understood by those folks.

I don’t believe that there is a technical solution to teaching, to running a school, to governing a district. Education is far too complex.

|

31 de maio de 2018

26 de maio de 2018

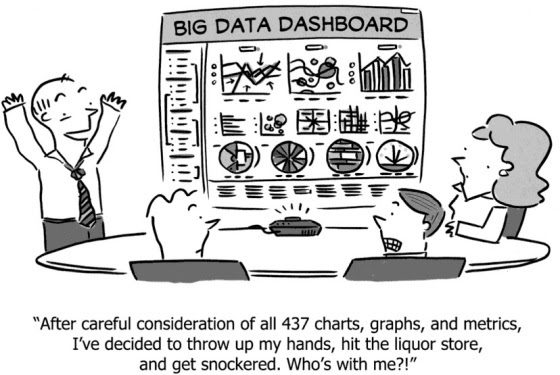

Cartoons on Using Data to make Decisions by larrycuban

|

| Thanks for flying with |

20 de maio de 2018

Democracy Prep: “No Excuses” Schools that Build Citizens? by larrycuban

|

| Thanks |

11 de maio de 2018

Can You Be a ‘Good Teacher’ Inside a Failing School? (JennyAbamu) by larrycuban

This article appeared in EdSurge, April 2, 2018

“Jenny Abamu is an education technology reporter at EdSurge where she covers technology's role in both higher education and K-12 spaces. She previously worked at Columbia University’s EdLab’s Development and Research Group, producing and publishing content for their digital education publication, New Learning Times. Before that, she worked as a researcher, planner, and overnight assignment editor for NY1 News Channel in New York City. She holds a Masters degree in International and Comparative Education from Columbia University's Teacher's College.”

Here’s a popular movie plot: Great teacher goes into a troubled neighborhood and turns around a low-performing school. Educators love the messages from these films, and even children are inspired. Unfortunately, many school districts never find the Coach Carters or Erin Gruwells who bring such happy endings. In fact, in a broken district such as Detroit’s, schools in hard-bitten neighborhoods sometimes go from “turnarounds” to closure.

Fisher Magnet Upper Academy is a middle school located within one of the toughest neighborhoods in the city, stricken with poverty and crime. In 2013, local news reportsnamed the area the third most violent zip code in America. In 2016, Fisher was named one of the 38 campuses at risk of closure after the Michigan legislature passed a bill saying any school ranked at the bottom 5 percent of state campuses for three years in a row would be subject to consequences.

Despite a relatively new building, constructed in 2003 as part of a former superintendent’s turnaround project, Fisher has suffered from consistent low performance—falling far below state standards on exams and adjusted growth targets designed specifically for the school. During the 2015-16 school year, only 0.7 percent (3 out of 451) of students met state standards in math, and only 4.5 percent met English Language Arts standards.

Carl Brownlee, a former United States Marine officer, is a middle school social studies teacher at Fisher Magnet Upper Academy. He has been teaching at Fisher for over 10 years. He believes changes in academic performance can happen in a struggling school like Fisher but says he has only seen it happen in the movies.

“The only person I have seen that had the ability change this type of climate and culture was Joe Clark, or Morgan Freeman in that movie, ‘Lean On Me,’” says Brownlee. That doesn’t mean he thinks improvements are implausible, though. He says: “I think there were some good ideas that movie that you could translate into schools.”

Brownlee believes that he is a good teacher, in spite of what test scores may reflect. And he feels as though his students have been slighted by ineffective teachers in the past. So he plans to stay at Fisher, where he hopes to bring advanced teaching skills to students that other educators may ignore.

“My children are being cheated because they are not given the same experiences as their counterparts in other schools, and that’s not fair,” says Brownlee. “That’s one of the reasons I stay where I am at.”

As students trickle in Brownlee’s classroom on a Friday morning, he stands by the door to greet each of them. He instructs them to grab their work folders and get into groups. The 6th, 7th and 8th graders entering Brownlee’s class in their uniforms are respectful, quiet and—though naturally distracted from time to time with whispers and giggles—appear to be on task. They ask questions and support one another as they move around in groups through learning stations Brownlee has set up in class.

Technology has a role to play in Brownlee’s effort as well. Using the free version of tools such as Edmodo, Kahoot, and Google Forms, Docs and sometimes Slides, Brownlee varies his lessons on topics such as Chinese history and the Missouri Compromise. He opens up classes with hip-hop education from Flocabulary, then goes into worksheets, videos, group assignments, and desktop assignments—incorporating cell phone apps and music in the activities. He constantly walks around the room, refocusing off-task students and offering feedback on their work. His classroom does not fit the “before” image in most romanticized school turnaround stories.

“The skill sets that I have, I like to use them with these young people instead of going to another school where you might get the test scores that people are asking for,” Brownlee continues, noting that he is not looking to teach the “ideal student” in an exemplary school. “My kids don’t come from that, so I try to hang in there and do my best. They need it. They deserve it.”'

By “doing his best” Brownlee means constantly learning, often looking for resources outside of the district for support. He is also trying to incorporate more personalization into his classroom, noting that the State Department of Education has embraced the implementation of such instructional models.

Since Fisher does not have enough Chromebooks for every student, teachers share a cart of laptops that travel from class to class. Teachers also combine technical and non-technical ways of personalizing instruction. For Brownlee, part of personalization means gauging the social and emotional well-being of students each morning, so he knows how to approach them throughout the lesson.

“Are they ready for school work? You might have [a student] come in who just had a loved one die the night before. We have had that on many occasions. They still come to school,” explains Brownlee. “You can’t just go into teaching when they come into the classroom if you don’t know where they are at.”

To meet students where they are, Brownlee has a couple of go-to tools. He uses apps such as Quizlet to encourage students to learn independently. In addition, he uses Edpuzzle when students are having a hard time with particular topics in class. The app allows them to rewatch annotated video lessons.

“I have done it with several of our resource students,” Brownlee explains, noting how one struggling 7th-grader has been showing improvement since using apps like Edmodo and Edpuzzle. “He comes to class every day, and you can see that he is trying. He wants to understand what is going on. He likes to look at the videos, and his effort is starting to show in his work. You get a little joy when you see them getting it.”

Brownlee also has digital portfolios that he uses to track student mastery and growth, something all teachers in his school incorporate. Yet, he notes that this method has yielded mixed results, particularly since many teachers serve a large number of students--and struggle to keep records up to date.

Brownlee works with 198 students daily and admits its difficult for him and other teachers to add student work to the portfolios consistently. “It’s just very difficult when you have so many students to try to personalize for each one,” he says. “You can tailor for each student, but only to a certain extent.”

Despite the difficulties, Brownlee has not given up trying to tailor instruction for his students. He makes time to celebrate the small gains he sees students making, like the lessons he teaches that students remember long after they graduate. But he admits that there are days that he gets tired, particularly noting the difficulties keeping up with changes in the district.

His district has flipped between state and local control over the years and has had a number of different superintendents and principals; most of them bring new initiatives with them. This school year Brownlee has a new superintendent and a new school principal, but real-world challenges facing students in and out of his school continues. He is cautiously hopeful that things can in improve, but the familiarity of changes that don’t yield academic results is haunting— causing him to work overtime with his happy-ending out of sight.

“No matter what you do you are still going to be accountable for the test score. It does not matter if the students just came from another school or district. It does not matter if they came to you four grades behind, if that child’s family is impoverished, or if the child has any type of learning disability that may be undiagnosed,” says Brownlee. “It is more like a professional football team. If the team does not win, it is the coach’s fault, and the coach is fired.”

larrycuban | May 11, 2018

6 de maio de 2018

Jean-Michel Blanquer: "La escuela debe transmitir los saberes fundamentales: leer, escribir, contar y respetar"

Ricardo Braginski, Clarin, 6-5-2018

El ministro de Educación de Francia impulsa una reforma desde la primera infancia. Y propone retomar estrategias pedagógicas clásicas, como el dictado y la memorización.

El ministro de Educación de Francia Jean-Michel Blanquer va contra toda regla del marketing político. Ganó popularidad entre los franceses hablando sobre “aprendizajes” y “ciencias cognitivas”, a tal punto que hoy es el funcionario con mejor imagen en el gabinete de Emmanuel Macron. Impulsa una ambiciosa reforma educativa, que se centra en el nivel inicial y los primeros años de la primaria, y que toma en cuenta la comparación internacional y la investigación, en particular las ciencias cognitivas. Estuvo en Argentina participando de las primeras reuniones del G20.

Señas particulares. Jean-Michel Blanquer es observado en todo el mundo por las reformas educativas que está llevando a cabo en Francia. En enero participó de un programa de política en la televisión francesa y su buena imagen se disparó. Salió en las tapas de distintas revistas, que lo presentaron como “la nueva estrella” o “el vicepresidente”. Antes de ser funcionario, Blanquer fue profesor y director de escuela. También escribió dos libros en los que detalla su propuesta educativa.

- La educación en Francia tiene similitudes con la Argentina: a más inversión no se consiguen mejores resultados. ¿Por qué sucede?

- Hay distintos factores. En primer lugar, la falta de atención que tuvo la primera infancia. Hoy vemos de manera muy clara que aquello que no se hace durante los primeros años de vida -hasta los 7 u 8 años- difícilmente se logre después. Y por eso hay que darle prioridad a lo que en Francia llamamos “la escuela maternal”, que va de los 3 a los 6 años. Con el presidente Macron decidimos que en Francia será obligatoria desde 2019. En la escuela primaria se debe transmitir los saberes fundamentales, que son leer, escribir, contar y respetar al otro.

Mirá también

Entrevista al rector de la UBA: "Si tomáramos un examen de ingreso hoy no entraría ni un 25%"

- ¿Tienen suficiente presupuesto para garantizar escuelas y docentes para todos los chicos de 3 años?

- Sí. Nos va a costar un poco, pero hoy más del 95% de esos chicos ya van a la escuela en Francia. Son más de 20 mil los que no van. Pero lo más importante es que va a haber un cambio cualitativo de esa escuela maternal. La vamos a pensar como una escuela del lenguaje. Porque, debido a las circunstancias familiares, la primera desigualdad que hay entre los chicos es la del acceso al lenguaje. La escuela maternal debe compensar eso, con juegos, música, métodos que permiten al niño enriquecer su vocabulario. Es clave para la adquisición de la lectura y la escritura.

Chicos jugando en el pizarrón de un jardín rodante.

- ¿Usted hizo críticas a la pedagogía de los últimos años? ¿En qué consisten y cómo lo piensan cambiar?

- La pedagogía como disciplina es clave para tener éxito en el sistema educativo. Creo que tiene que ir evolucionando con la práctica en el terreno y con investigación de alto nivel. Ahora hay una revolución científica, que es la revolución de las ciencias cognitivas. Sabemos muchas más cosas sobre el cerebro humano y los mecanismos de aprendizaje de lo que sabíamos diez años atrás. Entonces no podemos seguir con los mismos discursos sobre la pedagogía, que a veces se presentan modernos pero que no lo son. Hubo debates en Francia entre clásicos y modernos. Los que están a favor del esfuerzo y los que están a favor del placer. Estos dos aspectos no deben oponerse. Debe haber exigencia y al mismo tiempo benevolencia hacia cada chico. Hay que superar falsas oposiciones pedagógicas.

- ¿Por qué usted propuso volver al dictado y a la memorización?

- El dictado no es algo del pasado. Hay veinte maneras de hacer un dictado y todas pueden ser muy inteligentes. No tiene por qué ser aburrido: puede ser un juego. El dictado es un ejercicio muy útil para que el niño entienda la lógica del lenguaje. Puedo decir lo mismo sobre la memorización. El cerebro del niño es muy capaz, por ejemplo, de aprender otro idioma muy temprano.

Los expertos en educación debaten entre las formas de aprendizaje clásicas y modernas.

- Cómo tienen que ser formados y seleccionados los docentes?

- Todos los países necesitan que la profesión docente sea atractiva, porque el docente es clave. Una sociedad con buena salud es aquella donde el profesor es central, donde hay respeto hacia él por parte de padres, instituciones y alumnos.

- ¿Cree que el salario tiene que estar atada al rendimiento del docente?

- Lo importante dar incentivos cuando hacen algo especial, cuando van a los barrios difíciles, o en lugares lejanos. Para mí lo mejor sería entrar en una lógica donde haya recompensas no para un individuo sino para los equipos que alcanzan progresos.

- ¿Lo están implementando?

- Es una idea que se va a discutir en Francia. La profesión de profesor no es solo individual sino también colectiva. Sobre todo teniendo en cuenta que los alumnos deben ser vistos en su globalidad.

Jean Michel Blanquer, ministro de Educación de Francia (Juano Tesone).

- ¿A qué atribuye su popularidad?

- Bueno, la popularidad es algo muy frágil. Lo que me parece muy importante es que haya una fuerte confianza de la sociedad hacia la escuela. Ese es mi objetivo, más allá de los cambios políticos o pedagógicos. Es lo que le estoy diciendo a la sociedad francesa, y por eso tal vez tengo este apoyo. Me gustaría mucho, después de 5 años, poder decir que hemos creado un nuevo círculo virtuoso de confianza de la sociedad con sus escuelas. Los dos principales factores de éxito de un sistema educativo son la formación de los maestros y la buena relación entre las familias y la escuela.

- ¿Cree que puede llegar a ser presidente algún día?

-No, no es el objetivo. El objetivo es ser ministro de Educación.

Mirá también

Mercedes D'Alessandro: "Hoy tenemos feminismo en las calles, en la universidad y en los lugares de trabajo"

- ¿Qué puede aportar el G20 a la educación?

- La educación es un tema muy local, muy nacional y muy internacional, todo al mismo tiempo. Y no se oponen estas tres dimensiones. Es una cuestión cotidiana entre el maestro y el alumno, pero es también una cuestión mundial e internacional porque todos los países tenemos los mismos retos: qué hacer, qué transmitir, cómo concebimos la escuela en el mundo tecnológico, etcétera. El G20 puede ayudar a compartir lo que está bien en cada uno de los países.