*Dictionary definition of "mediocrity."

mediocrity (n.)

early 15c., "moderation; intermediate state or amount," from Middle French médiocrité and directly from Latin mediocritatem (nominative mediocritas) "a middle state, middling condition, medium," from mediocris (see mediocre). Neutral at first; disparaging sense began to predominate from late 16c. The meaning "person of mediocre abilities or attainments" is from 1690s. Before the tinge of disparagement crept in, another name for the Golden Mean was golden mediocrity.

*A parent in a suburban school district nervous about pressuring children to be the best,says:

Why are we pushing our kids to excel at just about everything? It’s no longer enough just to play town soccer; elementary schoolers also have to be on a year-round club team and receive private coaching. Your daughter’s getting As in math class? Time for an afterschool enrichment program to learn more-complex concepts—and might as well throw in tutors for reading, science, foreign languages, and dance for good measure. Every time I decide to let my 11-year-old twin boys and eight-year-old daughter find their own way, like my parents did when I was a kid, I get sucked back into thinking that I need to help them get ahead. No one wants her kid to be average anymore—at anything.

But to what end? Not every child is going to get into an honors class, or make the select team, or earn a spot in the ensemble—no matter how much money a parent throws at the situation. Is this endless quest for success contributing to our kids’ growing anxiety in ways that will affect them for years to come? Looking around at the children in Wayland, where I live, and the surrounding towns, I’m worried we’re headed in that direction---and I'm not alone.

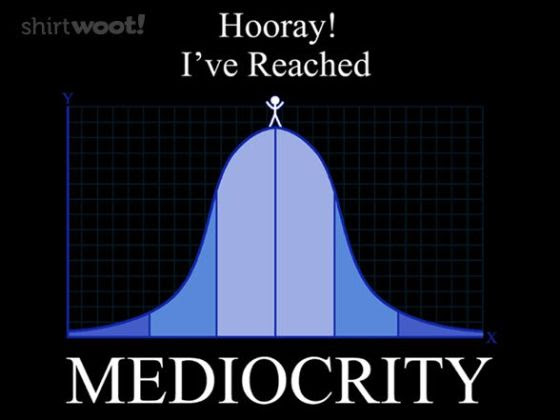

*Then there is a cartoon about the concept:

Ah, the bell-shaped curve that puts most of us in the middle with outliers to the left (talented and gifted?) and outliers to the right (dropouts and losers?). Being "middling" carries the odor of mediocrity in American thinking and practice. High quality is sacrificed to good enough. No one wants to be "middling." The above parent asks " why are we pushing our kids to excel at just about everything?"

Part of the answer to her question is that striving for success is as American as, well, apple pie. It is part of the core ideology of being American. Some individuals will rise to the top, be successful, by dint of hard work and talent; others, equally as hard working, settling in to the middle of the distribution, will not taste the sweet tang of success. It is a meritocratic system, many say. Sure, Americans want equal opportunity to succeed--another core value in the nation's ideology--but it is stellar performance that wins the gold medal, gets the Fulbright scholarship, and receives the Most Valuable Player award.

Every individual can't be excellent in a culture where intellectual, artistic, athletic, and creative talents are distributed unequally across the population. Especially when economic inequality, social discrimination, and who one knows continue to play a large part in divvying up success and failure. Yet calls for pursuing academic excellence in schools while maintaining equitable opportunity across the board in order for individuals to succeed rather than fail have spurred reformers time and again.

And it is that constant tension between the pursuit of excellence in individual performance and valuing equal opportunity that has given being in the middle--where most of us are--a bad name. Many call it mediocrity.

Not everyone can win but settling for less than excellence--being in the middle--is seemingly worse than losing. No one wants to be mediocre--say be picked last in a sandlot game or expected to do minimum work.

I do not find being in the middle shameful in a seemingly meritocratic society of winners and losers. Being "average" is not an epithet. Nor is it a compliment to anyone. Yet "mediocre" and "mediocrity" have become particularly useful words in the rhetoric school reformers use. Note the third sentence of the influential report, A Nation at Risk (1983).

We report to the American people that while we can take justifiable pride in what our schools and colleges have historically accomplished and contributed to the United States and the well-being of its people, the educational foundations of our society are presently being eroded by a rising tide of mediocrity that threatens our very future as a Nation and a people.

Authors of the report declare that U.S. students' low scores on international tests compared to students in countries that economically compete with America is evidence of that "rising tide of mediocrity." Or as the Report says:

If an unfriendly foreign power had attempted to impose on America the mediocre educational performance that exists today, we might well have viewed it as an act of war. As it stands, we have allowed this to happen to ourselves. We have even squandered the gains in student achievement made in the wake of the Sputnik challenge.

At that time and for the next 35 years, U.S. student test scores have ended up in the middle of all nations's students taking tests (see here, here and here). Being in middle of the international distribution of scores was and has been the basis of why reformers have said American schools are failing--see the age-old pattern described in Part 1 of policy elites creating a crisis in schooling and urging their particular solutions--and the need for higher graduation requirements, more parental choice, tougher academic standards, school accountability for student outcomes and better preparation for the workplace. Such reforms, these policy elites promised, will not only lead to better scores on international tests but knowledgeable and skilled graduates who can enter and succeed at entry-level jobs and strengthen the nation's economy. Has not happened yet.

Here is the twist that hurts policy elites who have religiously pursued the above "solutions" for the past three decades. With Common Core standards, higher high school graduation rates, more testing, and accountability still producing all of this "mediocrity" in international test scores, the current economy continues to expand, growth rates have risen, unemployment is low. The effects of the Great Recession of 2008 have dissipated (see here).

Yet, I have not heard a single word of praise from policy elite leaders for what part schools have played in this economic resurgence. Instead, criticism of public school "mediocrity" continues unabated.

|

18 de dezembro de 2017

Success, Failure, and “Mediocrity” in U.S. Schools (Part 2) by larrycuban

Postado por

jorge werthein

às

11:07

Assinar:

Postar comentários (Atom)

Nenhum comentário:

Postar um comentário