Some currencies lose weight on a diet of QE and cheap oil; others bulk up

TWO trends have dominated the world of burgernomics over the past six months: currency markets have bubbled like potatoes in a fryer as the oil price has fallen to finger-licking lows and central banks have cooked up new monetary stances. The currencies of commodity exporters have been burnt, while those of big importers have sizzled. Meanwhile, the end of quantitative easing in America has supersized the dollar, whereas the mere prospect of it in Europe has made a happy meal of the euro.

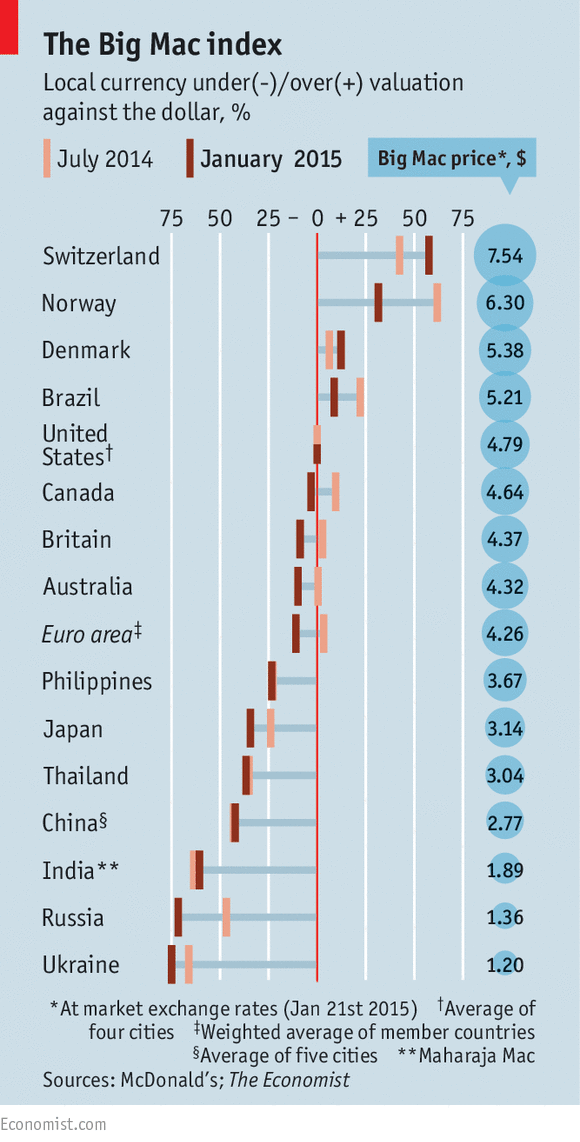

The Economist whipped up the Big Mac index in 1986 as a bun-loving way of explaining currencies’ relative values. It is based on the theory of purchasing-power parity, which posits that over the long run, currencies should adjust so that a basket of identical goods costs the same everywhere. We fill our basket with just one item: the Big Mac, which is made to the same recipe in almost all countries (India’s Maharaja Mac, a chicken sandwich, is an exception). Buying a Big Mac in Denmark, for example, costs $5.38 at market exchange rates compared with $4.79 in America, so our index suggests the Danish krone is 12% overvalued (see chart). No wonder Denmark’s central bank cut rates this week.

The few other currencies to have increased in value against the dollar since last summer are those of big energy importers, such as China and India. The currencies of several other import-guzzlers, including the Thai baht and the Philippine peso, have lost relatively little ground. By contrast, the currencies that have lost the most are those of big commodity exporters. The Brazilian real was 22% overvalued six months ago but is now only 9%. The Canadian dollar, the Norwegian kroner and the Russian rouble have also been quarterpounded. In a bid to fire up the Canadian economy, the Bank of Canada also cut interest rates this week.On average, Americans abroad get more burger for their buck than they did last summer. Relatively beefy growth in America has helped to fatten the greenback. Elsewhere, however, central bankers are still trying to add sauce to their economies, in part by encouraging their currencies to fall. In Japan, for instance, a belt-busting bond-buying scheme has caused the yen to waste away. The expectation that the European Central Bank would serve up a hearty dose of QE seems to have prompted Switzerland’s stomach-turning scrapping of the franc’s peg to the euro. Last week a Swiss Big Mac cost $6.38, but now it gobbles up $7.54.

But a weaker currency is not necessarily hard to swallow: it can help beef up exports and quench deflationary pressures. For years central bankers in Australia and New Zealand have found themselves in a pickle: high prices for the raw materials they sell have buoyed their currencies, to the detriment of other parts of the economy. The recent decline of both the Aussie and kiwi dollars is therefore something that policymakers from both countries have probably been looking forward to—with relish.

Nenhum comentário:

Postar um comentário