English pupils are the most tested in the industrialised world. The countries with the best education don't subject their kids to this misery

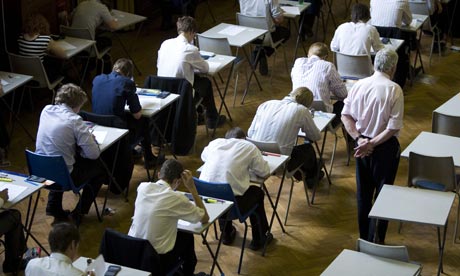

Schoolchildren sit an exam. Photograph: Rex Features

It was a sorry sight. On Thursday, the heads of England's four exam boards, as well as three of their examiners, filed into the Thatcher Room of Portcullis House to be quizzed by MPs on the education select committee. The examiners had been secretly filmed by the Daily Telegraph offering teachers advice on how to boost their exam results – from telling them which topics their pupils could expect to be tested on, to advising them on how to "hammer exam technique" – and subsequently suspended by their boards.

However, in the midst of their litany of excuses ("We all make mistakes," whined one examiner; "It was a throwaway figure of speech," wailed another), some revealing remarks were made. Mark Dawe, chief executive of exam board OCR, told MPs there is "an enormous amount of pressure on the system". Suspended examiner Paul Barnes admitted there are "pressures to raise achievements", and that it is a "competitive world".

They have a point. The corruption of the testing regime is only a symptom. The disease is the tyranny of testing itself; a culture of relentless exams, spurious league tables and artificial competition between schools. Our exam system isn't fit for purpose.

English children are now the most tested children in the industrialised world (thanks to devolution, their Scottish and Welsh cousins do not suffer the same burden of examination); the average pupil will be subjected to at least 70 tests during his or her school career.

This preoccupation with testing is bad for schools, teachers and pupils. For schools, the costs have ballooned: spending on exam fees nearly doubled, to over £300m, between 2002 and 2010. Astonishingly, exams now account for the second biggest cost to schools after teachers' pay.

For teachers, it is deeply demoralising and demotivating to have to "teach to the test", as so many of them are forced to do. For many, teaching has become dull, narrow and uninspiring. There is no reward for creativity, only results, results, results.

For pupils, high-stakes tests are a well-documented source of stress and anxiety. According to children's charities, this can physically manifest itself as sleep-loss, bed-wetting or skin disorders.

Critics of the current system abound, and include the education select committee, the Children's Society, the Royal Society and various academics. In 2009, for example, a Cambridge University review of primary education described national testing as "the elephant in the curriculum" and noted that in the final year of primary school "breadth competes with the much narrower scope of what is to be tested".

In his book Education by Numbers: The Tyranny of Testing, Warwick Mansell explains how a strategy of "pursuing results almost as ends in themselves has been forced on schools, in their desperation to fulfil the requirements of hyper-accountability". But, he writes, "this grades race is ultimately self-defeating. It does not guarantee better educated pupils, just better statistics for schools and the government." He documents how primary school pupils spend an average of 150 hours purely in preparation for the Sats tests: "England's education system is now an exams system," he says.

Mansell's book should be required reading for the test-obsessed education secretary, Michael Gove, and his Labour shadow, Stephen Twigg. Politically motivated meddling in the examination system, by both Conservatives and Labour, has done little to boost school standards or pupil performance. Over the past decade, according to the OECD's Programme for International Student Assessment (Pisa) global survey of 15-year-olds, Britain has slipped from fourth to 16th in science, seventh to 25th in literacy, and eighth to 28th in maths.

The OECD's Economic Survey 2011 points out how, in spite of school spending per pupil rising sharply over the past decade, improvements in educational outcomes have been limited, bolstered only by grade inflation. The OECD notes that "high-stake tests" have proliferated in England, and yet these can often "produce perverse incentives" and "lead to negligence of non-cognitive skill formation".

So what if we took a radically different approach? What if we scrapped all the endless exams, abolished the headline-grabbing school league tables, and freed our teachers to teach kids how to think instead of how to take a test?

Would our schools get better or worse? Finland provides a clue. The country has topped the various Pisa rankings over the last 10 years. But Finland has no league tables, no school inspections, no pupil-by-pupil tests. In fact, the first national test a Finnish child sits is when he or she is about to leave school, at 18. The government does carry out regular assessments of school performance, by testing representative samples of students, but these are only for internal use and the results aren't published.

The Finns prefer to empower their teachers, who tend to be better-qualified and better-paid than our own. But it's not just sandal-wearing Scandinavians. Take Japan. A recent report for the Japanese ministry of education said the country should "avoid school ranking and unhealthy competition". And in Shanghai, China, as Mansell points out, school-by-school exam results tends not to be published – yet this didn't stop Shanghai from taking the top spot in last year's Pisa rankings.

Here in the UK, though, we have fetishised exams and deified league tables; we have prioritised test results – statistics, numbers, scores – over the hearts and, crucially, minds of our children.

And to what purpose? Exams are means, not ends; they do not, of themselves, raise standards or produce better-educated children. Nor do they truly measure the qualities necessary for a well-rounded education – from independent reasoning to creative thinking. Instead, in the words of the US educational psychologist Joseph Renzulli, we have created a new version of the Three Rs: "ram, remember, regurgitate".

For far too long, the debate over exams in this country has revolved around "dumbing down". The issue, however, is not whether exams are easier or harder than they once were but what role they serve. To conflate mere test results with a high-quality education is to do a disservice to our children. The truth is that education by exam isn't an education worthy of the name.

Nenhum comentário:

Postar um comentário