As a recent school board member in a racially and economically diverse district, I know there has never been a tougher time for educators.

Schools are being asked to raise achievement and meet tougher standards, with fewer resources and diminishing paychecks. But in the midst of worrying about the Common Core and testing metrics, we need also to consider whether an issue too long seen as marginal – school discipline – is hampering our efforts to close the achievement gap.

The rate of suspensions has doubled since the 1970s to 3.45 million students in grades K-12 during the 2011-12 academic year, according to the Civil Rights Data Collection just released by the U.S. Department of Education. On March 13, a group of 26 education and behavioral health experts known as the Research-to-Practice Collaborative on School Discipline Disparities announced the results of a three-year research project, concluding that zero-tolerance discipline is neither effective nor fairly applied. (I am a co-founder and member of the group.) Here are details of our findings:

While bouncing disruptive students from the classroom can give exasperated teachers and classmates a needed breather, the end result is actually more misbehavior. Comparing schools with similar demographic characteristics, suspended students are more likely to reoffend, and schools with higher suspension rates do worse academically overall.

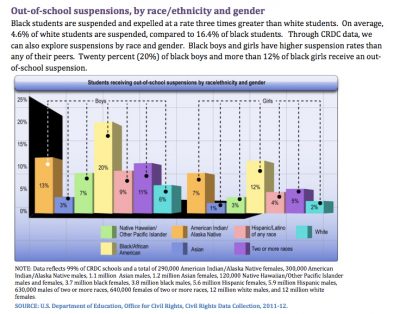

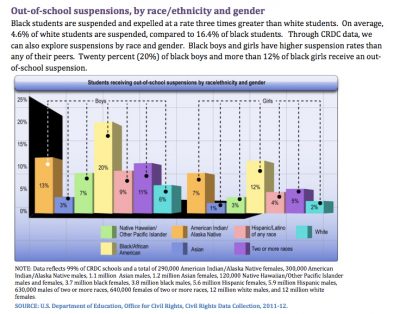

Most troubling, an overreliance on suspension excludes from instruction those children who can least afford to miss school. Black boys are four times as likely as their white peers to be suspended from school. Black and Latino children with learning disabilities are at highest risk of all for school removal. “Contrary to assumptions, this yawning disparity is not explained by poverty or more serious misbehavior by black students,” says Russell Skiba, Director of the Equity Center at the University of Indiana and the principal investigator of the Disparities Collaborative.

The consequences for student achievement are stark. A 2013 study by Robert Balfanz, a leading researcher at Johns Hopkins University on indicators of high school graduation, found that a single suspension in the 9th grade correlates with a doubling of the dropout rate, and tripling of the chances that a child will end up in the juvenile justice system.

Thus, at the very moment that changing demographics are forcing a rare convergence of education elites, community activists and corporate titans, all keenly focused on closing the minority achievement gap, our school discipline practices are undermining the very children we say we most want to help. There may be deep disagreement among these groups about the right approach to education reform, but one thing should be plain to everyone: no child’s learning ever benefited from a denial of instruction.

That is not to say educators should tolerate aggressive or disruptive behavior in school. Cursing out a teacher is demeaning, unacceptable and merits a meaningful corrective response. But what about that response, exactly? As one teacher I met at a U.S. Department of Education conference on school climate told me, “Ten-day suspensions – we dole those out like tic tacs. I’m here because I know there has to be a better way.”

Happily, there is a better way. The Disparities Collaborative also outlines several promising interventions to reduce the discipline gap:

Tanya Coke is a Distinguished Lecturer at the John Jay College of Criminal Justice in New York and a co-founder of the Research-to-Practice Collaborative on School Discipline Disparities. Until 2013, she was a member of the Montclair Board of Education in Montclair, New Jersey and the New Jersey School Boards Association’s School Security Task Force.

Schools are being asked to raise achievement and meet tougher standards, with fewer resources and diminishing paychecks. But in the midst of worrying about the Common Core and testing metrics, we need also to consider whether an issue too long seen as marginal – school discipline – is hampering our efforts to close the achievement gap.

The rate of suspensions has doubled since the 1970s to 3.45 million students in grades K-12 during the 2011-12 academic year, according to the Civil Rights Data Collection just released by the U.S. Department of Education. On March 13, a group of 26 education and behavioral health experts known as the Research-to-Practice Collaborative on School Discipline Disparities announced the results of a three-year research project, concluding that zero-tolerance discipline is neither effective nor fairly applied. (I am a co-founder and member of the group.) Here are details of our findings:

While bouncing disruptive students from the classroom can give exasperated teachers and classmates a needed breather, the end result is actually more misbehavior. Comparing schools with similar demographic characteristics, suspended students are more likely to reoffend, and schools with higher suspension rates do worse academically overall.

Most troubling, an overreliance on suspension excludes from instruction those children who can least afford to miss school. Black boys are four times as likely as their white peers to be suspended from school. Black and Latino children with learning disabilities are at highest risk of all for school removal. “Contrary to assumptions, this yawning disparity is not explained by poverty or more serious misbehavior by black students,” says Russell Skiba, Director of the Equity Center at the University of Indiana and the principal investigator of the Disparities Collaborative.

The consequences for student achievement are stark. A 2013 study by Robert Balfanz, a leading researcher at Johns Hopkins University on indicators of high school graduation, found that a single suspension in the 9th grade correlates with a doubling of the dropout rate, and tripling of the chances that a child will end up in the juvenile justice system.

You might like:

That is not to say educators should tolerate aggressive or disruptive behavior in school. Cursing out a teacher is demeaning, unacceptable and merits a meaningful corrective response. But what about that response, exactly? As one teacher I met at a U.S. Department of Education conference on school climate told me, “Ten-day suspensions – we dole those out like tic tacs. I’m here because I know there has to be a better way.”

Happily, there is a better way. The Disparities Collaborative also outlines several promising interventions to reduce the discipline gap:

- First, schools, states and the federal government need to improve data collection on school discipline, disaggregated by race, ethnicity, disability and where possible, LGBT status. Schools must then examine their data regularly to pinpoint and address the cause of inequities. For example, one school in California analyzed its data on dress code violations and found that minority boys were being disciplined more frequently and harshly for sagging pants, than were girls for short skirts.

- Second, schools should reconsider vague and subjective categories of offenses, like “disorderly conduct.” The Los Angeles Unified School District took an important step last year when it overhauled the discipline code to abolish suspensions for “willful defiance,” a category that accounted for half of all suspensions, often for minor misbehavior like refusing to take off a hat or give up a cellphone.

- Third, adults need to inquire why conflicts are occurring before imposing mandatory punishments. Sometimes, an unwelcoming climate fuels defiant behavior. In too many schools, students arrive not to a “Good morning” from staff, but to long lines at metal detectors in buildings that look and feel like prisons. In every school, students and teachers carry stress from home – a parent incarcerated, an acrimonious divorce – that translates to short fuses in class. Sometimes we just need someone to ask, “Hey, what’s eating you?”

- Fourth, the Disparities Collaborative determined that building relationships and involving young people in problem solving are key to reducing racial, gender and LGBT disparities in school discipline. Schools that use restorative justice principles – a method that convenes the offender, victims and peers to craft a response that focuses on repairing the harm and restoring the community – find that disciplinary infractions decline, as do rates of race and gender disparity.

- Finally, schools need funding for mental health and student assistance counselors, as well as coaching for all staff on classroom management and positive behavior approaches. Unfortunately, what schools are mainly getting in the wake of the tragic shootings at Newtown is funding for more school police. Imagine what good might result if we used some of that money, and some of those staff and child hours wasted in in-school suspension or Saturday detention, to conduct restorative justice circles?

Tanya Coke is a Distinguished Lecturer at the John Jay College of Criminal Justice in New York and a co-founder of the Research-to-Practice Collaborative on School Discipline Disparities. Until 2013, she was a member of the Montclair Board of Education in Montclair, New Jersey and the New Jersey School Boards Association’s School Security Task Force.

Nenhum comentário:

Postar um comentário