By Andrew Wyckoff,Director for Science, Technology and Industry, OECD

| The growing awareness that knowledge-based capital (KBC) is driving economic growth is prevalent in today’s global marketplace. KBC includes a broad range of intangible assets, like research, data, software and design skills, which capture or express human ingenuity. The creation and application of knowledge is especially critical to the ability of firms and organisations to develop in a competitive global economy and to create high-wage employment.

KBC allows countries and firms to upgrade their comparative advantage and position themselves in higher value-added industries, activities and segments of the global marketplace. Indeed, in global value chains, most of the value of a good or service is typically created in upstream activities where product design, research and development, and production of core components occur, or in the tail-end of downstream activities where marketing and branding are applied. For example, iPod production in 2006 accounted for 14, 000 jobs inside the United States and 27, 000 jobs outside. But American workers–those who contributed design, software and marketing expertise–earned $753, nearly twice as much as foreign workers who earned $ 318 million.

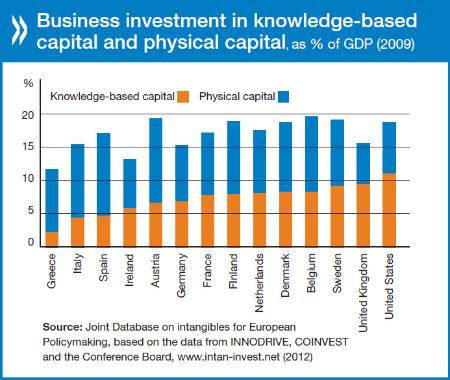

Ageing populations and dwindling natural resources mean that growth in advanced economies will increasingly depend on knowledge-based increases in productivity. Unlike labour, natural resources and physical capital, KBC is the only factor of production that will not suffer from scarcity. In many OECD countries, and for many years, business investment in KBC has increased faster than investment in physical capital such as machinery, equipment and buildings. Indeed, in the United Kingdom and the United States, investment in KBC now significantly exceeds investment in physical capital, and is strongly correlated with productivity growth. Both China and Brazil are also making concerted efforts to develop KBC to increase productivity and occupy higher-value segments in global production chains. Whole industries are being transformed by KBC. In the automotive sector, for instance, it is now estimated that 90% of new car features such as innovative ignition systems, improved fuel injection and safety cameras contain a significant software component. Up to 40% of all development costs associated with bringing a new model to the road can be attributed to electronics and software. It is striking that 10 of the largest automotive firms now have advanced research centres in Silicon Valley. OECD research also shows that countries that invest more in KBC are also the best at reallocating resources to innovative firms, the main drivers of employment growth in OECD economies. As a share of GDP, the United States and Sweden invest about twice as much in KBC as Italy and Spain, and their patenting firms attract four times as much capital.

Technology is both enabling and fuelling the trend toward more knowledge-based economies. The growing pervasiveness of the Internet means that personal and professional activities are increasingly conducted online, while new capabilities are simultaneously emerging to capture, analyse and store these interactions. The explosive growth of mobile networks, cloud computing and smart information and communications technology (ICT) applications (ie sensors and machine-to-machine communication) enables vast fields of information–loosely referred to as “big data”–to be processed, shared and transferred across the globe. These data are like raw material for innovative firms and forward-thinking governments, enabling significant value creation, social benefits and productivity gains.

The rise of KBC will require that policymakers update old policy frameworks better suited for a world in which physical capital had primacy. For example, years ago, intellectual property rights (IPR) were seen as a rather narrow and specialised policy area of particular importance to only a few sectors. But as we evolve into knowledge-based economies, copyrights, patents and trademarks are playing a growing role in protecting intellectual property and preserving economic investment. The recent smartphone patent wars between Apple and Samsung may be the most visible sign of this development. As always, policymakers must ensure that IPR systems keep pace with technological change and continue to facilitate innovation and competition. A word of caution is in order. The changes associated with KBC represent important opportunities to boost productivity. But they also come at a time of considerable structural change induced by the crisis and could, at least in the short run, further exacerbate issues of unemployment and inequality. The rise of KBC, for example, may involve technologies that displace human labour, particularly labour associated with low-skilled and routine tasks, and is prone to winner-takes-all opportunities for a tiny few. Future OECD work will address the interplay between KBC and income inequality and, more generally, policies for inclusive innovation. The message remains clear: to promote long-term growth and the jobs of tomorrow, governments must ensure a policy framework that helps businesses invest in KBC.

References and recommended sources

|

Nenhum comentário:

Postar um comentário