School league tables

The fall of a former Nordic education star in the latest PISA tests is focusing interest on the tougher Asian model instead

WHEN the first Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) tests to focus on maths results were published a decade ago, Finland’s blue-cross flag fluttered near the top of the rankings. Its pupils excelled at numeracy, and topped the table in science and reading. Education reformers found the prospect of non-selective, high-achieving and low-stress education bewitching.

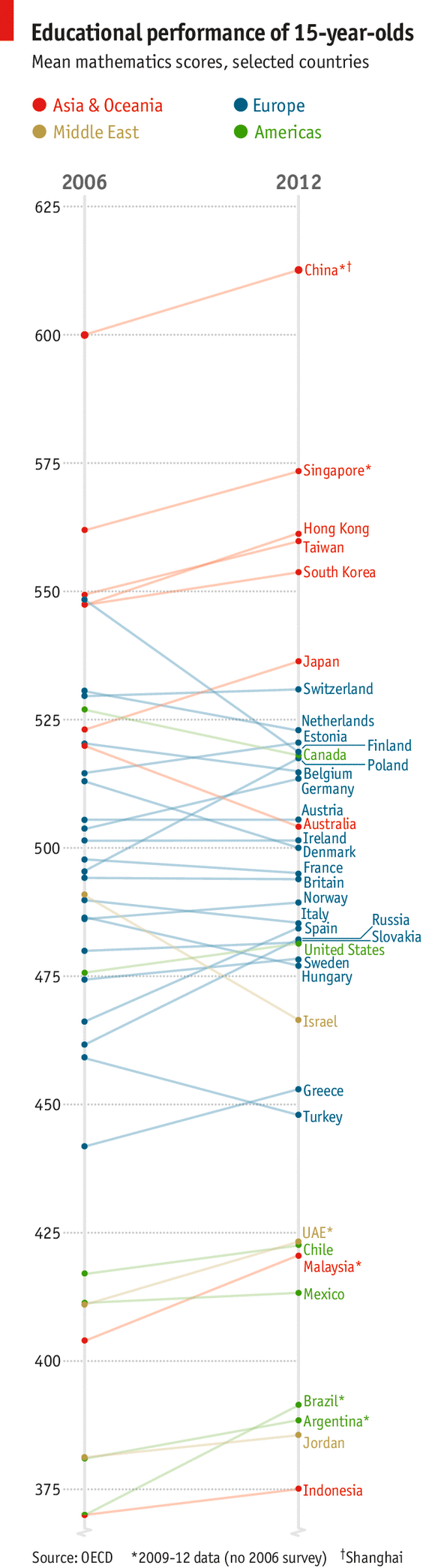

Every three years since then, 15-year-olds have sat PISA tests in maths, reading and science. In 2012 fully 500,000 heads were bent over desks for the exam in 65 countries or cities. The results, published on December 3rd, doled out a large helping of humble pie to Europe’s former champion. Finland has fallen by 22 points on its 2009 result, with smaller falls (12 points and 9) in reading and science. “The golden days are over,” lamented the Finnbay news website.

Leena Krokfors, an academic there, blames declining motivation and a failure of maths teachers and the curriculum to inspire enthusiasm. Others are beginning to wonder whether the egalitarian nature of Finnish education might be an underlying problem. Juha Yia-Jaaski, who runs a technology project to stretch the academically able, worries that a focus on raising the achievement of the majority of pupils shortchanges the cleverest. The country is “kidding itself”, Ms Jaaska says, if it thinks they can catch up at university.None of this should have come as a surprise. Finland’s maths performance has been tailing off since 2006. But it is worsening faster than in other countries with falling scores such as Canada and Denmark. The Asian high-fliers (Shanghai, Hong Kong and Singapore) have consolidated their position at the top. Much soul-searching is under way in Helsinki.

As Finns argue about how to retain their pre-eminence, many other countries in the West still envy it—as well as the progress of rapid improvers such as Estonia and Poland. France and Germany, in contrast, have flatlined. America’s dire showing led Arne Duncan, the education secretary, to decry “a picture of educational stagnation”, with Americans being “out-educated” by the Chinese. Some hope for a motivating shock like that delivered in 1957 by the Soviet Sputnik launch.

Get me into orbit

More important than individual country scores are the underlying trends. Asian systems are clearly no longer just hothouses for swots. Their best performers have briskly extended opportunity to children of poorer families, narrowing the achievement gap. Chinese officials say other big urban centres will emulate Shanghai’s stellar results by 2029.

Andreas Schleicher, who runs the PISA tests on behalf of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, a Paris-based think-tank for rich countries, notes that well over half of Shanghai’s pupils had a “deep conceptual knowledge” of maths, as opposed to around 13% in middling countries like Britain. That pertained even for those from disadvantaged backgrounds: “a remarkable performance”, concludes Mr Schleicher.

But the glory prompts questions. One concerns the psychological price paid. Asian children have a brutal load of after-school classes and the system is harsh on failure. Others question the methodology—some think that making education systems PISA-friendly has become a skill in itself. Scores do not show, for instance, how well pupils can apply what they have learned in later life.

Politicians claim that PISA justifies their particular selection of policies. Britain’s Conservative schools minister, Michael Gove, says the results vindicate his drive to change how schools are run, but his opponents argue that his beloved free schools, modelled on Sweden’s state-funded but independent Friskola, have not raised overall performance (Sweden fell well below the OECD average inoverall rankings.)

The structure of education systems seems to count for less than overall culture. England, Northern Ireland and Scotland have markedly different varieties of school—England has moved gradually over the past decade to greater managerial autonomy from local bureaucracies, Scotland retains a centralised system and Northern Ireland kept selective schools. Their results are very similar and none excel. Overall, Asians and eastern Europeans are improving much faster than America and western Europe, regardless of how schools are organised.

New education stars can emerge and old ones fade fast. But the broader lesson may be simple, if brutal. Successful countries focus fiercely on the quality of teaching and eschew zigzag changes of direction or philosophy. Teachers and families share a determination to help the young succeed. Vietnam is now in eighth place for maths, besting many rich countries which spend far more. Pushy parenting helps too. Half of all Vietnamese parents stay in regular contact with teachers to monitor their children’s progress.

Our "Daily chart" displays the results by overall ranking here.

Nenhum comentário:

Postar um comentário